CHAPTER V – PLOT IN COMEDY

In many respects the laws of structure determined for the serious

drama are equally valid for comedy, but there are also important

differences between the two kinds of dramatic creation. First, it may

be generally stated that in comedies the action of the plot is much

more independent of the characters than it is in the serious drama:

it is, as we have already implied, even possible to create a comic

plot which shall be really comic, while its persons are nothing more

than puppets, the development of the plot being wholly extraneous to

the characters. This is the case in The Comedy of Errors, in

much so-called farce, in much of the Spanish comedy. Again, the comic

action is far less bound to emphasize law in its treatment of events;

it can make free use of what we call accident and chance.

Passing now to a more detailed consideration of its structure, we

find that comedies fall into two main groups, according as their

comic interest does or does not determine the main plot. Compare, for

example, King Henry IV with Every Man in His Humour. In

the former there is a serious main plot, based on events in English

history wherein the fiercest passions were aroused and the largest

interests involved, and wherein the actors were of heroic type. The

comic interest is found in a number of interspersed scenes whose

action is loosely connected with the serious main plot; cut out these

scenes, and with few changes the play becomes a serious historical

drama. In Jonson’s play, on the other hand, the exact converse is

the case. The serious interest – and there is very little – is

subordinate. The comic interest is not merely developed in the main

plot, it actually constitutes it; cut out this and you destroy the

play.

These two plays may be accepted as typical of two great classes of

comedies. To those of the first type the name “romantic comedy”

has been given, for reasons not wholly connected with its structure;

those of the second type have been variously styled, according to

considerations foreign to this discussion. To it belong all of

Aristophanes, most of Plautus and Terence, most of Jonson and

Molière, the comedies of Massinger and Middleton and Congreve. With

Henry IV are to be classed all of Shakespeare’s comedies

except Love’s Labour’s Lost, The Comedy of Errors,

The Merry Wives of Windsor, The Taming of the Shrew.

Since the romantic comedy has as its basis a serious main plot,

and its comic interests are episodic, it may be temporarily

disregarded. It is in the second class of comedies that we shall find

the typical comic structure.

Reverting to our illustration of the primitive form of comic plot,

– our case of the man who sits down on the floor, – let us start

again from this. In actual life we know that this may occur for

various reasons: (1) he may have miscalculated the position of the

chair, and the fault is therefore his own; or (2) the chair may

break, and the fault is no one’s; or (3) some one with malice

prepense may have pulled the chair from under him, or may have placed

a weak chair where he was likely to sit.

So in comedies. The action may be one where the mistakes, the

comic disappointments, arise out of the weakness of the victim, and

he alone is to blame, or they may spring from circumstance, and no

one is responsible, or they may be deliberately planned by one of the

play’s persons, an arch-intriguer, assisted, perhaps, by lucky

accident, which he knows how to turn to account.

An example of the first sort is seen, though not with perfect

clearness, in Love’s Labours Lost, through the fourth act.

The four gentlemen have simply miscalculated their own powers and

attempted something beyond them. Hence, all fail signally, and the

great scene for which the play is planned, IV, 3, merely presents

this failure. Each does in turn expose his fellow, in true

“house-that-Jack-built fashion,” but no one of them has planned

the downfall of another.

The second kind is exemplified with typical clearness in The

Comedy of Errors. Here the whole complication is the result of

chance, no one guides its progress, and its conclusion is as much

accident as any part of its course.

The third sort is seen, as has just been said, in the last act of

Love’s Labour’s Lost, but it is better to select an

instance where the entire play is constructed on this principle.

Among the multitude of such, we may mention, as being, for one reason

or another, unusually good instances, Jonson’s Every Man in His

Humour (Brainworm and Ed. Knowell are the intriguers); The

Silent Woman (arch-intriguers, Dauphine, Clerimont, and Lovewit);

Chapman’s All Fools (intriguers, Rinaldo, for the main plot,

Cornelio, for a subordinate counter-plot); Massinger’s A New Way

to Pay Old Debts (intriguers, Wellborn, for the main plot,

Allworth and Lovell for the underplot); Molière’s L’École

des Maris (intriguers, Isabelle and Valère). Among them, the

simplest in structure is Molière’s, and next comes Massinger’s,

which we will take as a type because it is English. The argument is,

briefly, as follows:

Act I. Wellborn, a prodigal, has ruined himself by his

excesses, and his estate has passed into the hands of his uncle,

Overreach, an unscrupulous old man who has amassed large wealth by

sharp practice. In despair, Wellborn turns for help to Lady Allworth,

a rich widow whose late husband he had once befriended in time of

need. Out of gratitude for this, Lady Allworth consents to feign a

betrothal to Wellborn.

Acts II, III, and IV. On the strength of his expectations,

Wellborn is instantly restored to credit. His uncle is anxious to

facilitate the match, hoping ultimately to get hold of Lady

Allworth’s wealth as he already has got Wellborn’s. He therefore

pays his nephew’s debts and entertains him royally.

Overreach has a daughter, Margaret, whom he longs to see married

to a title, and he offers her in marriage to Lord Lovell. In the

lord’s service is young Allworth, stepson to Lady Allworth, who

loves Margaret and is loved by her. Lord Lovell befriends his cause,

and while feigning consent to the marriage for himself, helps young

Allworth convey Margaret away and marry her.

Meanwhile Marrall, an attorney and an unscrupulous attaché of

Overreach, decides that it will be more profitable to serve Wellborn.

Act V. Through Marrall’s agency it is discovered that the

deed transferring Wellborn’s estates to his uncle is worthless, and

the ownership, therefore, reverts to Wellborn. Next, Overreach learns

of the marriage of his daughter with young Allworth. At the double

catastrophe he goes mad.

Now, it will be seen that the entire structure of the plot depends

on the deliberately planned schemes of Wellborn and Allworth to

outwit Overreach. Does this differ from the plan of the serious

drama?

In a sense, we might adopt the phraseology of the tragedy, and

call the action “a losing struggle, by an imperfect character,

against the overpowering forces of life.” We might say that there

is found here, the three things essential to tragedy: suffering,

struggle, causality.

In a sense, yes; but in a sense so different from the tragic that,

though the words may be unchanged, the ideas can no longer be treated

as the same.

First: the character is indeed imperfect, but the imperfections

are here regarded as material for comic contrast, and subjects for

judicial reprehension, not for pity and sympathy. This has already

been discussed.

Next, as to the struggle. The result of it in both cases is the

overthrow of some one, but the process is different in principle and

significance – as different as is our case where the malicious

person pulls away the chair from the case where two men grapple in a

fair fight. In the serious drama, the hero is contending, it may be

against one man, it may be against a host, it may be against himself,

it may be against the remorseless “course of things.” We may even

know from the beginning that the struggle must end in failure, as we

do know in the Oedipus, or in The Cenci; but our hero

really fights, he has his chance, all his energies go into the

struggle and are staked on the issue. In this kind of comedy, on the

other hand, he does not really fight; he is a victim, his overthrow

is not really inevitable, it is artfully prearranged.

Finally, the causality in the two kinds of drama is totally

different. Tragedy must be based on law, and, as we saw, it is better

for the tragedian not to use such events as have about them an air of

chance. For comedy this requirement is not imperative. The main thing

is the presentation of striking incongruities, and we do not care

whether these are evidently grounded in the law of the universe or

not; in fact, the range of comic view being limited, it is often

better that it should not call too vividly to mind the iron rule of

law. Accordingly, we find in comedy the widest license allowed. When

Shakespeare, borrowing for his use the old story of the twin

brothers, complicates its situations by postulating a second pair of

twins as servants to these brothers, we do not cavil at the

improbability. If he chose to postulate two pairs of twin sisters,

too, we should not object, provided he was master of his material.

These considerations have, as will appear, an important bearing on

the nature of the comic catastrophe.

So much for general questions. Contrast now more particularly the

plans of the two types of drama:

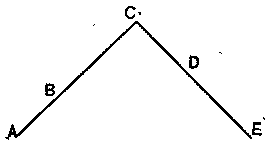

The serious drama usually begins in an apparent equilibrium, from

which the conflict develops. In the first part of the play, one of

the two contending forces is paramount; in the second, the other, and

the outcome is a final equilibrium wholly different from the apparent

equilibrium at the beginning.

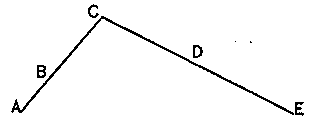

In the comedy just summarized the case is quite different. Instead

of an aggressor meeting an aggressor, there is an aggressor and a

victim. It is the natural result of the difference in principle

between comedy and tragedy. Instead of a conflict of forces, the

comic plots of this type present a process rather like the picking of

the lock of a safe; it may be interesting, it may involve great

ingenuity and address, but it is on a wholly different basis.

To pursue, for a moment, the figure of the lock: the beginning of

the play presents the problem; we see the strong safe, with its lock,

apparently secure; we see the would-be lock-breaker, his eyes fixed

on the safe, his fingers twitching to get at its secrets. Next, it is

hinted that despite this seeming security there are weak points –

possibly the lock can be forced. Then comes the process of forcing

it, until finally the successful lock-breaker carries out his scheme

and enjoys the fruits of his ingenuity.

What the corollaries are, which may be deduced from the

fundamental difference between the two problems, will be evident if

we consider, one by one, the logical divisions of this type of drama.

[1] Exposition. This has no peculiar features. In the

Massinger play, the first act is mainly expositional, the rising

action being only suggested at the end of the third scene.

[2] Exciting Force and Rising Action. The exciting force is

always found in the resolution of the arch-intriguer to outwit his

victim. In the play before us, it is Wellborn’s desperate resolve

to have one more try at fortune. Sometimes, as often in the plays of

Plautus and Terence, a preliminary action is presented, which is the

immediate occasion of this resolution, e.g. a young man falls

in love, and plans how to circumvent his father, who opposes him. It

is evident that, if in such a case the love-plot is given serious

enough emphasis, and our attention is drawn to the issues therein

involved, and away from the circumventing of the authorities

considered in itself, the play may become serious instead of comic.

The emphasis is laid, not on the intellectual problem, but on the

emotional crisis. This comes near being the case in As You Like

It; it is the case in Romeo and Juliet, and perhaps the

impression of weakness left upon us by the last act of this play is

partly due to this resemblance between its plan and that of the

ordinary comedy; for its tragic catastrophe is brought about, not by

the essential constitution of things and the nature of the spiritual

problem in itself, but by the accidental failure of an ingeniously

arranged scheme which might just as well have been successful.

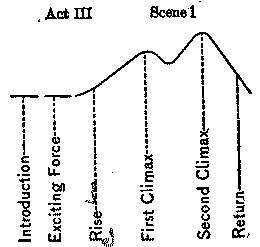

[3] Climax, and [4] Falling Action. There is,

strictly speaking, no climax and no falling action. For, from the

very nature of the case, the victim cannot retaliate; it would spoil

the play if he did. The movement of the rising action goes steadily

forward through the play, though not necessarily at uniform rate.

From the standpoint of the intriguer, it might be represented by a

line trending upward; from the standpoint of the victim, by one

trending downward. In the Massinger play, there is no climax, in the

sense in which we have hitherto been using the term. The only

possibility of making one would be to take it as formed by Act III,

Scene 2, because this scene is the most elaborate one in the play,

and the only one in which both main plot and subplot are interwoven.

But such an external test is not the sort one uses for tragedy.

[5] Catastrophe. It presents the completed results of the

intriguer’s plans, and the total overthrow of the victim. In

contrast to the tragic catastrophe it need not be causally determined

by what has preceded. Here, as elsewhere throughout the action,

causality is not emphasized, and here as elsewhere chance may

determine the issue. Thus, in the play mentioned, one-half of the

misfortune of Overreach is due, not to Wellborn’s machinations at

all, save very indirectly, but to the “Deus ex machina” in the

person of Marrall. Nor need the catastrophe have any quality of

finality; it is sufficient that it furnish some sort of finish, which

may not preclude further activity, renewed machinations, more

victimizing, or even a later “turning of the worm” in a

retaliatory stroke. Whereas tragedy must be final, comedy need not be

more than provisional; it offers a solution only of the specific

problem presented. Not that its conclusion is bound to be

provisional; this will depend partly upon what has been the

underlying purpose of the intrigue. Compare, as illustrating this,

the character of the conclusion in A New Way to Pay Old Debts,

which is approximately final, with that of The Alchemist,

which impresses one as not more than provisional. In many cases, it

is true, an air of conclusiveness is given by a sweeping moral

regeneration of all knaves, taking place in the last act, but this is

usually specious and unsatisfying; it is always quite different from

the fundamental and absolute readjustment in the true tragic

solution.

These are the chief differences to be noted between the comic and

the tragic plot. Subordinate differences will, of course, follow as

corollaries, but to take them up here would involve detailed analysis

of comedy after comedy. The essential thing is to have marked the

principal lines of divergence in the two types.

There are, indeed, cases where the lines seem to cross, and

perhaps really do so. In Othello, for example, we have an

action which conforms, in some respects, rather to the comic than the

tragic type. Othello himself is less a fighter than a victim, while

Iago’s attitude from the beginning is that of the arch-intriguer in

the comedies we have been discussing. He considers himself injured,

as does Wellborn; he plans a deliberate attack, as does Wellborn, and

enlists the help of others; he chooses the point where his victim is

weakest and makes his assault there, appealing to Othello’s

impulsive and unreasoning love, as Wellborn appeals to his uncle’s

consuming greed of gain. There is, moreover, in Iago’s attitude a

kind of grim, colossal humor, while in his scheming there is a cool,

if somewhat crude, power that makes us respect him and wins our

intellectual sympathy, as does the arch-intriguer in a comedy. The

divergence from comedy is found in the fact that (1) the character of

the victim is so noble, and is so treated as to evoke our emotional

sympathy; and (2) that he is strong enough, when finally aroused, to

retaliate with terrible energy and with such terrible effectiveness

that our thought is drawn away from the intellectual phases of the

case to its emotional issues. [1] But, great as these differences

are, the similarity in plan of the first four acts can scarcely be

ignored, and it may be one reason why the play does not appeal to all

of us as being tragic in the highest sense.

[1 Compare the case of Shylock, in The Merchant of

Venice, where the feeling toward the victim may range, according

to the character of the audience and of the actor, all the way from

pity to scornful derision.]

To take an instance of the converse: Molière’s Le

Misanthrope seems, to some readers at least, not at all the

typical comedy, and if we examine the plan of the plot we shall find

that it has traits distinctive rather of tragedy than of comedy; it

presents, namely, a real conflict of forces, and one that is grounded

in the spiritual nature of the persons concerned. With very slight

changes it might have been made a tragedy, and as it is, when read in

some moods, it is apt to seem more tragic than comic.

To resume: the plan of the comic action differs decidedly from

that of the serious drama in the character of its conflict, in its

freedom from the necessity of emphasizing law and its consequent

license in use of chance or accident, in the absence of a true climax

and a true falling action, and in the nature of its catastrophe. If

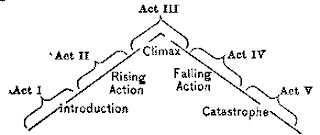

the serious drama is represented by the projected pyramid, the

comedy, such as Massinger’s, may be represented by two lines, an

ascending one for the intriguer, a descending one for the victim.

Applying these results to other comedies, it will be seen that

they conform fairly well. In the comedies of Plautus the victim is

usually a rich old man, the intriguer usually his son or nephew,

always assisted by a slave, and often by some other young man. The

differences between play and play are found in the differences in the

method of attack and in the motives for it. In Jonson’s comedies

the plan is the same in principle, but the schemes are exceedingly

complicated; there are usually several intriguers with plans somewhat

opposed, and there results a number of separate little puzzles, with

separate solutions, but all finally brought together in the general

solution of the dénouement. Molière’s plots, again, are more

simple. [1]

[1 For a fuller discussion of this type of comedy, cf.

Woodbridge, Studies in Jonson’s Comedy.]

Turning now from this large group of comedies, let us see how far

its principles apply to the group loosely classed as “romantic.”

At the beginning of the chapter we turned away from these because the

other, by virtue of its simplicity and its clearness of definition,

lent itself more readily to analysis. The results thus gained may

help us in dealing with the more difficult and elusive “romantic”

comedy, or, at least, may afford a firm base from which we may

proceed to its investigation.

In the intrigue comedy it was noted that, in supplying the

intriguer with a motive for his scheming, the love-interest was

usually employed, and it was suggested that if the love-interest was

sufficiently emphasized it might overbalance the comic interest, and

the play might become more or less serious. In turning from the plays

of Plautus to those of Terence one notices, in some cases, a tendency

toward this very thing. Terence’s more delicate talent seems to

have inclined him to lay a slightly greater emphasis on the serious

element of the plot, and there results a change in the proportionate

values of the serious and the comic elements. It varies in different

plays, but on the whole it seems fair to say that Terence treats the

motive-interest, if we may so distinguish it from the

intrigue-interest, with a tenderness of touch and gentle delicacy of

sympathy that in a later age would have developed into the so-called

“romantic” plot. In the Heautontimorumenos, the remorseful

old father doing self-imposed penance for his harshness toward his

son, the devotion of that son to his mistress, Antiphila, the little

touches that sketch the character of the girl Antiphila herself; in

the Andria, the overwhelming love of Pamphilus and Glycerium,

which seems to have in it something more than the passion we find

depicted in Plautus; – these give us glimpses, though no more than

glimpses, of a possible development into another sort of comedy.

Such a development is found in full maturity in the work of

Shakespeare; and though we may not take the plays of Terence as a

link in an actual evolutionary chain, – for the evolution took

place on other lines, – we may use them in our own thought as

furnishing a transition phase between the two kinds of comedy. [1]

[1 In Italian comedy, however, there seems actually to

have been some such evolution. Cf. Violet Paget’s Studies

of the Eighteenth Century in Italy.]

In dealing with Shakespeare we have, it must be remembered, only

approximate dates, and cannot base too much on chronology, yet enough

seems established to give us some rough notions of grouping and

development. The comedies, following the approximate chronology now

agreed upon, may be arranged as follows:

- Love’s Labour’s Lost.

- The Comedy of Errors.

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona.

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

- The Merchant of Venice.

- The Taming of the Shrew.

- King Henry IV, two parts.

- The Merry Wives of Windsor.

- Much Ado about Nothing.

- As You Like It.

- Twelfth Night.

- All’s Well that Ends Well.

- Measure for Measure.

- Cymbeline.

- The Winter’s Tale.

- The Tempest.

Of the earliest group two, Love’s Labour’s Lost and The

Comedy of Errors, have been already accounted for. In both the

comic interest determines the main plot, which is in the one case

developed out of the characters, in the other out of pure incident

apart from character. Yet in the latter case it is significant that

Shakespeare, using Plautus’ plot, added to it here and there

touches of seriousness not in his original, and the proportions of

the two elements in the play are more nearly as in some of Terence’s

comedies.

In The Two Gentlemen of Verona we have the romantic comedy

proper: there is the comic episode, which could be cut out without

maiming the play’s structure, and the serious love-plot, double (as

often in Terence) and following in its logical divisions the lines of

the serious drama. Because it is so simple and typical, it is worth

while to examine it somewhat in detail.

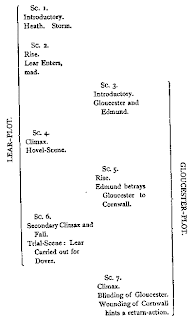

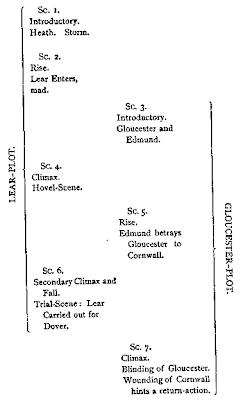

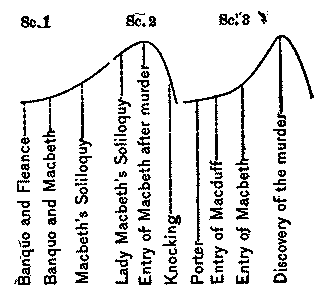

Act I. Exposition: love of Proteus and Julia,

friendship of Proteus and Valentine.

Rising Action: Valentine leaves for Milan, Proteus also is

to be sent thither.

Act II. Exposition, continued: love of Valentine and

Silvia.

Rising Action, continued: in development of Proteus’

treachery toward Julia and toward Valentine. A possible opposition is

hinted in Julia’s resolution to go to seek Proteus.

Act III. Climax: apparent success of Proteus’

plans, and banishment of Valentine.

Act IV. Return Action: turn of fortune for Valentine

suggested in his being made king of the outlaws; for Proteus it is

suggested by the appearance of Julia in Milan; for both it is

precipitated by Silvia’s plan to run away.

Act V. End of Return Action, and Resolution:

Silvia’s flight accomplished, the pursuit of her brings about the

solution.

Here it will be seen that there is a true conflict of forces, a

true rise, turning-point, and descent. And if Proteus has some of the

characteristics of the arch-intriguer, it is the serious, not the

comic aspect of his activity that is emphasized, and its criminal

nature.

The broad comedy in the play is embodied in the episodes where

Speed and Launce appear. They could be cut out, yet they are really

related to the main-plot scenes. For, as the Greeks used to follow up

their tragedies by a comic parody, so Shakespeare seems here to have

intended a parody of his own serious situations. In II, 2, is

presented the parting of the two lovers; in the next scene Launce

appears and sets forth, with the help of his slippers and his cane,

his own farewell to his family: the tears of his parents, the wails

of his cat, and the unnatural indifference of his “stony-hearted

dog.” Again, in III, 1, immediately following upon Valentine’s

desperate grief at the separation from Silvia, comes Speed with the

announcement that he, too, is in love, and he proceeds to discuss the

situation. The parallelism may be accidental, but it can scarcely be

deemed so. A similar case occurs in Love’s Labour’s Lost,

in the Armado-Costard-Jaquenetta episodes, while in As You Like It

the parody is elaborated, in Touchstone and Awdry, past the point of

mere parody, almost into an independent sub-interest.

But, besides this burlesque treatment of the serious issue, there

is, in the presentation of the issue itself, the beginning of a kind

of comedy peculiar to Shakespeare, namely, a touching of the serious

with a slightly comic light, – of the most tenderly delicate sort,

it is true, but unmistakable comedy nevertheless. This is the case in

the scenes in which Julia appears (note especially Act I, Scene 2).

It is the first trace of the author’s power to look at things in

two ways at once, a first gleam of the genius that was later to look

at the old Lear through the eyes of the “bitter fool,” and utter

his tragedy in a jest, “And yet I would not be thee, nuncle; thou

hast pared thy wit o’ both sides, and left nothing i’ the

middle”: (Goneril enters) “here comes one o’ the parings.”

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, again, there are the two

distinct lines: one the love-interest, – double again, and as usual

with the lines inter-crossing until straightened out by Oberon, –

and the other the comic interest in the tradesmen of Athens and their

interlude. The third group, the fairies and Puck, brings in a

semi-lyric element foreign to our present discussion. So far all is

clear: the comic in the tradesmen’s scenes is easily placed, and it

does not affect the main plot. But once more, in this main plot, we

find the note of comedy even stronger than in The Two Gentlemen of

Verona, while in the entire treatment there is a tone of

whimsicality that is perhaps a result of the midsummer night’s

witchery. The serious and the comic standpoints are represented for

us in Oberon and Puck, as they look on at the confusion of the two

pairs of lovers. Oberon, taking it earnestly, thinks of the

consequences:

“What hast thou done? Thou hast mistaken quite

And laid the love-juice on some true-love’s sight:

Of thy misprision must perforce ensue

Some true love turned and not a false turned true.”

Puck, the mocker, enjoys the situation:

“Captain of our fairy band,

Helena is here at hand;

And the youth, mistook by me,

Pleading for a lover’s fee.

Shall we their fond pageant see?

Lord, what fools these mortals be?

Oberon. Stand aside: the noise they make

Will cause Demetrius to awake.

Puck. Then will two at once woo one;

That must needs be sport alone;

And those things do best please me

That befall preposterously.”

And again, when Oberon reprimands the imp:

“This is thy negligence: still thou mistakest.

Or else committ’st thy knaveries wilfully.”

Puck answers, unabashed:

“Believe me, king of shadows, I mistook.

. . . . . . . . .

And so far am I glad it did so sort

As this their jangling I esteem a sport.” [1]

[1 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, III, 2.]

And evidently the poet himself was able to see at once with the

eyes of Oberon and of Puck.

In The Merchant of Venice a sterner note is struck. As

always, there is the episodic comedy and the love-plots, but there is

also the Shylock-Bassanio interest. And here the query intrudes

itself: did Shakespeare mean the Shylock plot to be comic or not? It

has, indeed, even now a grim kind of comic effect, but we must

suspect that the Elizabethan audience laughed where we do not.

Possibly Shakespeare meant him to be comic, and without purposing to

do so lapsed occasionally into a sympathetic treatment simply because

he could not help doing this with any character that he handled long.

This would account on the one hand for the hardness of tone in the

Jessica plot, and on the other hand for the sympathetic insight in

such passages as Shylock’s magnificent outburst in answer to

Salarino:

“Salar. Why, I am sure, if he forfeit, thou wilt

not take his flesh: what’s that good for?

Shy. To bait fish withal: if it will feed nothing

else, it will feed my revenge... I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes?

hath not a Jew hands... If you prick us, do we not bleed? if you

tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison us, do we not die? and if

you wrong us, shall we not revenge?” etc.

[1 The Merchant of

Venice, III, 1.]

According to this interpretation, we see in Shylock, despite such

passages, our familiar comic victim, grown indeed more formidable,

and requiring, not the justice but the injustice of the law courts to

overcome him, but the comic victim nevertheless, whose downfall, as

in typical comedy of intrigue, brings with it the happiness of the

lovers. Shakespeare’s mistake, then, was in making us sympathize

too keenly with Shylock, though, as we have said, this may not have

been the case for his own day.

This brings us to Henry IV, whose structure we have already

settled. For, though the character of Falstaff really overshadows the

entire play, it does not affect its structure, and the comic scenes

are episodic.

In The Merry Wives of Windsor we have a unique case: the

episodic comedy of the two preceding plays is, by a tour de force,

made the main plot of this one, while a serious subplot is added. The

victimizing is an end in itself, instead of being, as in the usual

comic main plot, a means to some other end; and Falstaff, from a

unique comic hero, has deteriorated into a commonplace comic butt. He

has lost his peculiar wit, and – most impossible of all – he

takes himself seriously, so that instead of laughing with him we are

laughing at him. The character of the play bears out the tradition

concerning its writing; it is evidently a piece of hack work, and

though the hack work of genius cannot be ignored, the play may, in

the present discussion, be set one side.

The next three comedies form a closely related group, which need

here scarcely be considered apart. All have serious love-plots and

all have comic by-play, that in Twelfth Night being curiously

affiliated with the type found in Molière and Jonson, while in

Rosalind we might, if we chose, see an arch-intriguer turned somewhat

ethereal and exceeding moral, managing the others for their best good

and her own innocent amusement. In all three the serious plot is

occasionally given a comic tone, the comedy being also partly

perceived even by the participants themselves. In these three plays

we get the perfection of the Shakespearean comedy, and we need not go

on to the last two groups, for, though the bitter jests of All’s

Well that Ends Well and Measure for Measure and the

idyllic temperateness of The Tempest show a tremendous range

in tone and many interesting points of detail, there is nothing new

in underlying structure.

Pausing here, then, and looking over the range of Shakespearean

comedy, we find certain qualities characterizing it: a main plot

embodying the love-interest, and episodic scenes embodying the comic

interest, the love-interest tinged with comedy yet not so as to

destroy its seriousness. It is thus allied with both kinds of drama:

with the serious, in that its main ends are serious and its use of

the emotions is so; with the comic by reason of this touch of comedy

in the treatment, and also by its emancipation from law. For these

serious plots have in this respect almost as much license as has pure

comedy, and, whereas tragedy is grounded in the spiritual laws of

human life, these present to us situations constructed by the fancy

and imagination from materials furnished by human life. In the

reconstruction, certain things are left out, and that which is above

all emphasized in tragedy is here steadily ignored, the binding force

of the law, – “Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.”

The imagination is free to work, and in the result there is an

element of the fanciful, even of the whimsical.

Thus, of the three forms, tragedy, comedy, and this Shakespearean

type of comedy, each selects out of life certain parts – no one is

complete. Comedy is, in one way, the most limited in its view and the

most superficial, it emphasizes certain intellectual phases of things

but leaves out others, and it avoids an appeal to the emotions;

tragedy is the deepest, laying stress on the emotional phases of

life, but treating them not simply in themselves, as does the lyric,

but in their relations to will and to outer fact. The romantic comedy

is somewhere between these two extremes: its treatment hovers between

the surface view, which is characteristic of the comic, and the

deeper insight that is essential to the tragic; it makes use of the

emotions, but ignores their causal relations.

It will be evident that this intermediate position gives the

fullest possible scope to the poetic imagination, and we see how in

The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream it almost

passes out of drama proper and verges on what we might call free

dramatic fantasia. It is because of these qualities, too, that it is

to the lover of the drama peculiarly satisfying. It has neither the

thinness that often characterizes pure comedy by reason of its

preponderating intellectuality, nor the almost oppressive emotional

intensity of tragedy; yet it is free to employ the resources of both

tragedy and comedy, while it may range in tone from the temperateness

of the epic to the emotional depth of the lyric. It has at once

richness and delicacy; it is at once philosophical and fanciful; it

is the most “poetic” of forms. Even Jonson, the high priest of

the intellectual in drama, when, for the only time in his dramatic

career, he gave freer play to the other side of his nature, adopted a

form akin to this; and Shakespeare, though his mightiest achievements

are in tragedy, attained in this form his most nearly perfect

artistic excellence.