CHAPTER II – LOGICAL DIVISIONS OF THE ACTION

Whatever be the disposition of the contesting forces, certain things in the working out are unvarying. There is always a rising action, there is always a falling action, no matter to which of these the chief activity of the hero is relegated; there is always a turning-point and a catastrophe; there are certain other minor but essential elements. It is well to consider these before we take up the more mechanical divisions of acts and scenes, and they will be discussed under the heads: Introduction, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, Catastrophe.

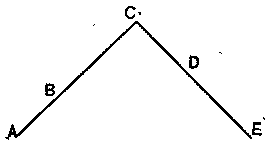

And, first, it will be well to look for a moment at the diagram which has, since Freytag presented it, become stock property in dramatic exposition. The play is represented as a pyramid, rising to its turning-point or climax and falling to its catastrophe. The metaphor will be found to be a helpful one. When the climax occurs at about the mechanical middle of the play, the diagram may be made thus (in the diagrams, A = introduction, B = rising action, C = turning-point, D = falling action, E = catastrophe):

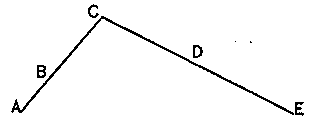

while, according as it falls before or after this point, we may modify the figure thus:

or thus:

indicating in the one case a rapid rising action and a slow descent, and in the other the reverse. Othello is, in one interpretation, an example of the last, if we make the steps of the rising action the successive scenes in which Iago arouses and fixes the jealous suspicion of Othello. According to this, Scene 3 of Act III is only one member of the ascent, which rises further in Scene 4 of the same act, and culminates in Act IV, Scene 1. The falling action may be said to begin in the same scene, where Othello, deeming his fears confirmed, first strikes Desdemona. This places the turning-point appreciably beyond the middle of the play, and gives a relatively short and abrupt descent. [1]

[1] Introduction. The introduction, whose purpose is to prepare the listener for the play, used often to be set apart from the play itself as a prologue, or given by one of the actors in a set speech. It is by Shakespeare incorporated into the tissue of the play, and forms the first scene, or occasionally a scene-group. There are certain things which it must do, and others which it may do. It must, quickly and deftly, put the hearer in possession of enough facts to make him intelligent in following the play. It must tell him who the speakers are and prepare him for those who are soon to enter; it must at least hint to him the place and time of the action, although this duty is much lightened by the extensive use of scenery on our modern stage. Besides this, it may set the tone of the piece, indicate its “stimmung,” thus throwing the sensitive listener into the right mood, much in the same way that the “vorspiel” to some operas does (instance that to Lohengrin and to Parsifal). But not all dramatic introductions are thus successful. As instances where they are so, may be mentioned the witch scene in Macbeth, the scene of the mob in Julius Caesar, of the night watch on the battlements in Hamlet, of the street brawl in Romeo and Juliet.

[1 Cf. supra, p. 73, and infra, p. 84.]

It is evident that the management of the introduction is a severe test of the author’s skill. He must tell his audience a great deal without seeming to tell them anything. To this end various devices have been employed. We are familiar, on our modern stage, with the chambermaid who vivaciously chronicles the family history as she dusts the family apartment; another resource, often used by the Elizabethans, who had not discovered the chambermaid, is that of the friend just returned from abroad, who must be told all the news. Some such expedient the author is almost forced to employ, even at the risk of seeming “stagey,” and few indeed are the plays whose beginnings have not some trace of effort and artificiality; for there is one thing more fatal to a play than artificiality, and that is obscurity. The audience must at any price be made to understand what they are witnessing, and be made to do it with the least possible effort on their part, so that even the boy in the gallery is quite clear in his mind. Under the most favorable conditions, it will always be a rather trying interval, this process of comprehension, and the habitual reader of plays is often conscious of a sinking of the heart as he is confronted with a new set of “dramatis personae.” Many of Shakespeare’s beginnings are not wholly successful: instance the first scene of Hamlet, whose perfection is destroyed by Horatio’s tedious account to Marcellus of the political relations of Denmark. Good beginnings are those of Macbeth, I, 2; Othello, I, 1; the first part of the opening scene in Coriolanus, the whole of the first scene of Romeo and Juliet, and of Julius Caesar. It is an interesting study to go over some of these scenes and see just how much information we have been given, which is absolutely needed to understand the play, and how deftly and without effort this has been accomplished.

It is almost a rule of the stage that the introduction shall prepare the audience to receive the hero, but that the hero himsejf shall not appear. Where the scene is a long one, this is not so necessarily the case, and the hero often enters toward its close (see the opening scene or scenes of Julius Caesar, Macbeth, Hamlet, Othello, Romeo and Juliet, Coriolanus). On the other hand, King Lear plunges at once into the action – for the few preliminary speeches of Gloucester can scarcely be counted – since, by good fortune of the plot and the author’s skill in taking advantage of it, there was no need of a preliminary exposition.

In a few cases, moreover, the hero appears at once, and the reason for this is easily apparent. Thus, in Richard III, the first monologue of the king is typical of the way in which his personality dominates the whole drama. Iago’s part in the first scene of Othello may be similarly interpreted, if we take the play as having a double hero, and the difference in their respective activities will account for the introduction of Iago and not Othello into the first scene. Compare, too, the different effect of Marlowe’s Jew of Malta, where the Jew himself is at once introduced to us, and Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, where he does not enter until the second scene. There is a corresponding difference, which it is hard to think accidental, between the parts played by the two men in the respective plays, and the attitude of the two authors toward them.

[2] Rising Action. After the introduction comes the action proper of the play. It begins with what is called the “exciting force,” that is, the force which is to change things from their condition of balance or repose, and precipitate the dramatic conflict. From the moment of the exciting force to the moment of the turning-point, the activity thus begun, be it that of the hero or of the opposition, must show a continual, though not necessarily an even-paced, gain in power and reach. We have noted how this continual rise is illustrated by Macbeth: the first two scenes form the introduction, and the third scene, Macbeth’s meeting with the witches, furnishes the exciting force. Here first is suggested to him the thought that afterwards develops into act, in the murders of Duncan and Banquo, while the fulfilment of the first two of the witches’ prophecies, at the end of the same scene, serves to emphasize their authority. From this point through to the turning-point we have a series of scenes, each of which advances the action somewhat, each carries Macbeth and his wife more and more irretrievably forward along the path they have chosen. The only exception is Act II, Scene 4, which is, also, the only one which does not bring forward one or both the protagonists. The scene is perhaps introduced to suggest the beginning of the return action, and, rather curiously, it is balanced by Act IV, Scene 1, where Macbeth’s baleful activity overlaps into the return action. This is only another instance of the singularly symmetrical structure of the play. [1]

[1 Cf. supra, p. 70.]

But the rising action ought also to introduce the opposing forces and make the audience familiar with the characters in which they are embodied, although it is left for the second part of the play to give them greater prominence. Thus, the flight of Malcolm to safety in England hints at a future opponent to Macbeth; Macduff’s refusal to go to the coronation of Macbeth at Scone is significant; the failure to kill Fleance suggests the possibility of further checks; the refusal of Macduff to come to court emphasizes his hostility already shadowed. By this means we are prepared for the return action even before it has actually set in; we are constantly reminded that this seeming success is perhaps only strengthening the hand of avenging fate, that “God is not mocked”; and we are thus, in the first part, kept from forgetting what in the second part is to be borne in upon us with tremendous force, namely, the universality and inviolability of law.

[3] Turning-point or Climax. At a certain point in the rising action a moment comes when the activity of the aggressive force is completed; a moment after which the reversal begins, and there looms into view the force that is to dominate the last half of the action. This point is the climax, or, better, the turning-point of the play. It is, of course, possible intellectually to separate this climactic point of the rise from the initial point of the fall, but actually the two moments are often found organically united in the same scene or scene-group. If the play is of the first type, the turning-point will be the moment when the hero completes the accomplishment of his purposes and feels the check of opposition. Thus in Macbeth the banquet-scene begins with the news of Banquo’s death, which assures the usurper that his most dreaded rival is removed. But with the news comes the first check, “Fleance is scaped,” and this is followed up by the appearance of Banquo’s ghost, foreboding the retribution to come. The two following scenes may be considered as complementary to this, but they are, very properly, less elaborated, and are transitional to the return action. [1]

[1 Cf. supra, p. 70.]

In the second type of play, the turning-point shows the converse of this, and represents the hero as passing from a state of relative quiescence to a state of activity. Thus in Othello the great scene, III, 3, between Iago and Othello makes the beginning of the turn, though here again we ought perhaps to make a two-membered climax, consisting of this scene plus the first scene of Act IV to the word “Devil!” spoken by Othello to Desdemona, and the blow that goes with it. In a play where the struggle is subjective, and both the contending forces are lodged within the hero himself, the turning-point should be the moment when that force which is ultimately to conquer first gains its decided supremacy. Of this type is Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, a play which, however, illustrates dramatic principles as much by their breach as by their observance. Its theme is the struggle between passion and honor, but in the actual working out this theme is obscured by the crowd of unessential details. Its turning-point should come at the point where passion conquers. There are two places where this point might be said to be: first, in Athens, when, after the departure of Octavia as mediator to Caesar, Antony returns to Egypt and Cleopatra; second, at Actium, when Antony flies, following the galleys of Cleopatra. In Shakespeare’s play the first of these two points has been wholly ignored, the second has been very inadequately treated. The battle itself is given to a messenger to describe, and the following scene, III, 2, supremely impressive as its first part is, is not enough. It would have been right if set in a larger scene-group, like some of the scene-groups in Hamlet or in Julius Caesar; but, taken as a single one out of the thirteen scenes of which this act is composed, it is artistically inadequate, out of proportion. It is, of course, not necessary that the climax be a scene of great outward magnificence, though, in fact, it often is so (cf. Macbeth, Julius Caesar), yet a certain outward impressiveness is, after all, requisite, simply because, as we have seen earlier, the drama deals solely with the phenomenal. It cannot, as do Ibsen and Maeterlinck in some of their later and more extreme works, deal apparently in commonplaces and expect us to read into these the most supreme spiritual verities. It cannot, as does Shakespeare in this play, scatter half a dozen superb scenes through a play that has a total of forty-two, and leave the hearer to choose these half dozen to remember. The dramatist should expect much of his audience, but not so much as this. He should do his own selecting, his own emphasizing, for herein lies the difference between the raw material and the art-product.

On the other hand, the turning-point or climax must be spiritually emphatic as well as outwardly imposing; the climax in Macbeth is not the climax in virtue of presenting a royal banquet with rich, massive effects; that in Julius Caesar is not so in virtue of its impressive massing of senators assembled in the capitol of the world. There must be inner significance as well, as in these cases there is. So, too, the climax need not be the mechanical middle of the play; it must be its spiritual centre, the point toward which it makes from the beginning, and from which it passes downward to the end.

[4] Falling Action. What the exciting force is to the rising action, that the tragic force is to the falling action. It is, as we have seen, often closely united to the climax; sometimes they are, in a sense, one and the same, as in the Oedipus Tyrannus, where the very announcement that seems to make him perfectly secure really precipitates the discoveries that end in the catastrophe. However this may be, the tragic force is the initiation of the counter activity that is to govern the second half of the play and bring about the catastrophe. In Macbeth, as we have seen, it is tripartite; [1] in Romeo and Juliet it is dual, being embodied in the authority of the state and of Juliet’s parents; note that here one of these two – that of the state – is emphasized before the climax, the other follows immediately upon the climax, being incorporated in the same scene with it. These two forces are the occasion of the lovers’ ruin – the occasion rather than the cause, for the causal connection is, after all, indirect, and if the falling action in the play has a weakness, it is in this fact, – the fact, namely, that the forces of the falling action are not the forces that bring about the catastrophe. [2]

[1 Cf. p 70.]

[2 Cf. infra, p 145]

If, as is commonly the case, the play is of the first type, and the hero has been prominent in the first half of the play, the falling action will bring forward the characters of the opposition, and the hero will either be in the background, as in Macbeth, or, if this is not the case, his treatment will be different, as in Romeo and Juliet.

The management of the falling action offers peculiar difficulties. Up to the climax there has been growing suspense. After the tragic force appears, and the development of the opposition has begun, the listener begins to foresee what is to come, his mind naturally plunges forward, and he is impatient if the dramatist’s exposition be slower than his own thought-processes. It is like being forced to await the completion of a slowly spoken sentence, whose point we have already anticipated. Perhaps this is the reason why the turning-point and tragic force are often put late in the play, making the actual duration of the return action less than that of the rise. But there is another device for breaking through this over-confident expectancy of the listener. It is the insertion, in the midst of the falling action, of an event which for a moment breaks its advance, seems even to turn it back; there is shown a way of escape for the victim, or at least a jutting crag by which he may delay his fall. This is called the “final suspense.” Instances of it are: the victory of Antony in Antony and Cleopatra, IV, 7; the successful carrying out by Romeo and Juliet of all the first part of their scheme; the remorse of Edmund in Lear, V, 3, which moves him to revoke his order to kill Lear and Cordelia; the news brought to King Richard in Richard III, IV, 4, that the army and navy of his opponents are both scattered; in Julius Caesar, taking the first part as a whole in itself, Caesar’s determination not to go to the senate house that particular day.

Thus the dramatist, having throughout labored to impress upon us the inevitableness of fate, now for a moment reverses his methods and tries to undo all this. But only for a moment; the check has done its duty by keying up the slackened attention, and this done, the action swings back to its true movement and plunges forward to the catastrophe.

[5] Catastrophe. We have traced the dramatic struggle through its rise, turning-point, and fall. We now come to its termination. In our ordinary thought, the catastrophe is taken as almost synonymous with death, and this is based on a true conception. For the drama deals with human life, and death is, for the dramatist, the end. It is the fitting conclusion for the tragedy because it really concludes – it is final, precluding possibility of amendment or reprieve.

Evidently, however, its true character depends, not on itself, but upon the nature of the action which it concludes. Death is in itself always solemn, it often moves to pity, sometimes to horror; but it is tragic only when it comes as the natural, the inevitable conclusion of a tragic struggle. And in such cases the death itself will often actually seem a relief, just because it does terminate the struggle, just because it has been felt to be inevitable and so its occurrence relaxes the strain of expectation. This is the case in Macbeth. After the horror of the hero’s life, its baleful activity without, its moral disintegration within, the physical conflict at the end comes as a return to health. Macbeth himself feels it. After the first sinking of heart that comes with the loss of his last support, there follows the rebound, the natural, if desperate joy in a fair fight, and there is a ring of freedom in his last defiance:

“Lay on, Macduff, And damn’d be he that first cries, Hold, enough!”

Similarly, Brutus certainly feels death to be a release as he says:

“Caesar, now be still: I killed not thee with half so good a will.”

In King Lear the consummation of the tragedy is, it is true, in a death; not, however, Lear’s death, but Cordelia’s, and this is tragic, not as it concerns Cordelia, but as it touches Lear himself. The climax of “pity and fear” is in the sight of the mad old man, with the strength of despair, carrying in his dead daughter to show to all men, – the sight of him as he holds the feather to her lips to reveal her breathing, and, dim-eyed in the flesh, sees, with the vision of fevered desire, faint tokens of life. The tension breaks, and he dies, but his death is not tragic. It completes the tragedy of his life, and is fit, right, necessary; but for him it is a release. Kent’s feeling is ours:

“Vex not his ghost: O, let him pass! he hates him much That would upon the rack of this tough world Stretch him out longer.”

But death is often, too, the consummation of the tragedy in another way. In Antigone, the young girl’s death is the tragedy, because it marks the completeness of her subjugation to crushing human law; whereas the deaths of Haemon and of Eurydice, in so far as they are tragic at all, are so not in themselves, but in their effect on Creon. In Romeo and Juliet the deaths of the two lovers constitute the tragedy because only thus is forever shut off the possibility of recovered happiness.

What the catastrophe must bring about is not primarily death, but finality, – an equilibrium of forces which shall convince us of its permanence, It may be compared to the crash of the landslide by which the too precipitous cliff regains a natural slope. In Julius Caesar there may be said to be two points of catastrophe: the first for Caesar, the second for the conspirators. In the first half of the play, Caesar falls because he had risen too high; Brutus and Cassius, representing the norm, pull him down. But then they in their turn rise too high, and the second half of the play shows how they are therefore in their turn overthrown.

In the management of the catastrophe, more than anywhere else, there should be concentration, both of thought and expression. During the earlier part of the play, much elaboration is possible, much incident, much working-up of character and episode; but as we near the close the lines should narrow. Earlier, many outcomes were possible; now nothing is possible except the single end to which everything has been tending. Upon this the rays must all converge, everything subsidiary must be eliminated. And if the drama has been well motived and well constructed, there will be no need for elaboration, or even for much emphasis. The end is inevitable, all it requires is bare statement. To give more than this, to attempt explanation and commentary, implies carelessness on the part of the author, or a lack of faith in his work. Of carelessness, we have an illustration in the last lines of Julius Caesar, the conversation between Messala, Strato, and Octavius, concerning the promotion to favor of Brutus’ servant. It is a petty detail, that spoils the simple greatness of the close. In another way, the concluding lines, given to Octavius, will, to some of us, seem another dissonance. The play naturally ends with Antony’s words, “This was a man,” and we would fain rest here. Octavius’ cold words point forward into a new realm of life, and at the moment when we ought to feel that all is finished, we are reminded of the political rearrangements to come, the division of spoil – things which are historically true enough, but which are here not fitting. Perhaps it was Shakespeare’s optimism that moved him to make this sort of mistake as often as he did, but if so it was optimism ill-timed.

Summing up: we find that the action of the drama falls naturally into two parts, a rise and a fall; that the rising action has four parts: the introductory exposition, the exciting force, the working out, and the climax or turning-point. The falling action has three parts: the tragic force, the working out, and the catastrophe, while often the final suspense makes a fourth part.

Often, however, dramatic critics make a three-fold division instead of a twofold, namely, into the rising action, the climax, and the falling action. But if the climax is organically developed out of the rising action, as it ought to be, it is organically a part of it and should not be separated from it, even in thought.

These, then, we have called the essential elements of the drama, in distinction from those mechanical divisions, called acts and scenes, of which the dramatic structure is made up.