CHAPTER III – THE MECHANICAL DIVISIONS OF THE DRAMA

(1) The Acts

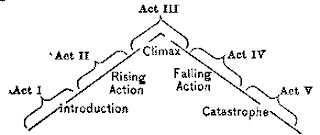

We have called the division of the play into acts and scenes a mechanical one, in distinction from the logical division which has just been discussed. The single fact that the five acts of a play are commonly of about equal length would make it antecedently improbable that they should correspond to the organic articulation of the action’s parts. That they actually do not so correspond will be evident from the most superficial inspection of any play. For the first act does not cover the introduction alone; the second act does not suffice to contain the rising action, which begins in the first act and overlaps into the third; the third act almost always contains the climax, but it also includes the penultimate stages of the rising action and the initial stages of the falling action; the main part of the falling action is contained in the fourth act, but its last part runs over into the fifth act, which is therefore not exclusively devoted to the catastrophe.

The relation between the mechanical and the logical divisions of the play may be thus diagrammed:

It might seem, then, that the acts have no organism in themselves – that they are merely marked off with a tape at equal distances in the course of the play. This is not altogether the case. The division into acts is indeed somewhat a matter of stage convenience: it gives the audience time to relax, and the actors time for rest or for change of costume, it furnishes opportunity for extensive scene-shifting. Moreover, from the author’s point of view it is useful because it gives him a few points in the action wherein, the continuity being completely broken, he may assume greater changes and longer lapses of time than is advisable between scenes.

But each act ought to be, to some extent, a whole in itself; it ought to have a “beginning, middle, and end,” a rise and fall somewhat like the rise and fall of the drama as a whole. In the Greek tragedy the sections of the action falling between the choruses formed such wholes, while in the Senecan tragedies, whence modern drama took its formal five-act structure, each act is distinctly complete in itself. In the Medea, for example, the five acts present each a distinct stage of the action. Disregarding the choruses, they may be thus epitomized:

Act I. Presents Medea’s turbulent mood as she realizes that she is about to be deserted by her husband.

Act II. Stirred by the bridal chorus, she meditates revenge, but does not yet determine on whom it shall fall. In order to perfect and carry out her yet immature plans, she obtains leave to remain in the palace one day longer.

Act III. Her anger increases and hardens into cold resolve. In an interview with Jason she assures herself that he really loves the two children he has had by her. She therefore decides to kill them, as well as Creusa, his new bride.

Act IV. She invokes the aid of magic to endow with destructive powers the rich gifts she purposes to send to Creusa. Her incantations finished, she sends the gifts by her sons.

Act V. A messenger announces that Creusa and her father have died in agony, and that the city is in flames. Medea, rejoicing in this first fruit of her vengeance, proceeds to complete it. One of her sons she kills before his father arrives, the other she kills in Jason’s presence. She herself departs in her magic chariot.

It will be seen that each act makes one step in the course of the action, each is dominated by a distinct mood in Medea herself: in the first act, it is half-dazed surprise and anger; in the second, wild rage and fierce longing for vengeance; in the third, hard and deliberate resolve; in the fourth, the elation of conscious power; in the fifth, exultation in completed vengeance, alternating with horror at her own deeds.

Each act, moreover, besides completing its section of the action, points forward, at its close, to the action that is to follow. Thus at the end of Act I comes her dark prophecy that, as through crime she entered the house of Theseus, through crime she will leave it. At the end of Act II this is made more definite when she gains the day’s reprieve in which to work out her vengeance. At the end of Act III she suggests the details of the plot she is to carry forward in the next act. At the end of Act IV she sends the fatal gifts, and we wait for Act V to learn the result.

Turning now to the modern drama, we find that the structure of the classic French plays is closely similar to their Senecan models. But with Shakespeare the case is different. Of no one of his plays can such an epitome as the one just given possibly be made. The acts have no such unity; instead of presenting a single step in the action, a single mood in the protagonist, they are a network of activities, a complex of moods.

Yet in some cases a kind of unity is discoverable. This is especially true of Macbeth. Here, the first act shows Macbeth yielding to the evil promptings of ambition, while Duncan’s visit gives him the opportunity to follow out his desires. The second act centres about the murder of Duncan. The third act presents the consummation of Macbeth‘s plots and the beginning of the reaction. The fourth and fifth acts, which are, as is usual with Shakespeare, not so well constructed, present the preliminary and the final stages of the reaction. Take now, in greater detail, the third act:

Scene 1. As a kind of introduction, Banquo sums up Macbeth’s course hitherto:

“Thou hast it now: King, Cawdor, Glamis, all As the weird women promised; and, I fear, Thou play’dst most foully for’t——”

Part 1. Then his mind reverts to the part of the witches’ oracle which has concerned himself. This second thought strikes the keynote of the act, since it is the memory of that prophecy which leads Macbeth to plan Banquo’s murder.

Part 2. The court enters, and Macbeth enjoins Banquo to be back for the night’s feast. His emphasis on Banquo’s return – “fail not our feast,” “Adieu, till you return at night” – points forward with double irony, first, to the measures Macbeth is about to take that Banquo may not “return at night,” and, second, to the terrible manner in which the murdered man is, after all, to fulfil the king’s injunction.

Part 3. Then follows the interview between the king and the murderers, really a scene in itself, with its own introduction (lines 73-85), rise (86-115), climax (116-126), and conclusion.

Thus the scene falls into three parts, an introduction, a transitional part, and a last part forming the first link in the rising action of the act.

Scene 2. This scene is chiefly of value as character-exposition. It does not advance the story. The opening words again insist, like the repetition of a theme in music, upon the Banquo motive:

“Lady Macbeth. Is Banquo gone from court? Servant. Ay, Madam, but returns again to-night.”

Then follows the interview between Lord and Lady Macbeth, giving the necessary insight into their desperate moods. The phrases, “these terrible dreams that shake us nightly,” “the torture of the mind,” “life’s fitful fever,” “O, full of scorpions is my mind,” are needed to give the spiritual atmosphere of the act. The scene ends by reverting to the theme with which it began.

Scene 3. The murder of Banquo. The escape of Fleance is the first check to Macbeth’s plans.

Scene 4. The banquet-scene. It is in three parts:

The brilliant introduction emphasizes the king’s royal state. The few words with the murderer serve to set Macbeth’s mind at rest as to the success of his plot against Banquo.

With the entrance of the ghost the change comes, and there follows the half-crazed agony of the king, and the hurried breaking up of the banqueters.

The last few lines of the scene sketch the after-mood of the king, varying between remorse and a feverish and desperate resolution.

This scene is, of course, the climax of the act, as of the play. It presents the consummation of the king’s plans and the beginning of the reaction. If we seek a turning-point in a few lines, we might find it in these, where he seems dimly conscious of the nemesis to come:

“the time has been,

That, when the brains were out, the man would die,

And there an end: but now they rise again,

With twenty mortal murders on their crowns,

And push us from our stools.”Scene 5. The witches and Hecate plan to draw on Macbeth “to his confusion.”

Scene 6. The two lords hint their suspicions with regard to Macbeth, and speak of the party Macduff is raising for resistance.

Thus the act has a regular rise and fall. It rises to the murder of Banquo, the escape of Fleance suggests the turn, while the banquet-scene and the two following scenes develop the threefold character of the reactionary forces, the forces, namely, of the moral order, of the supernatural realm, and of the political world.

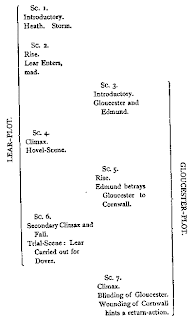

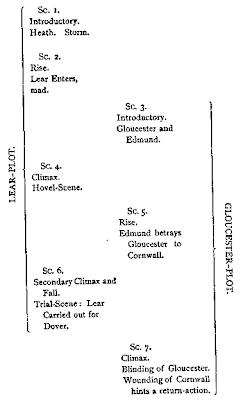

In Lear, Act III, there is, considering the complicated nature of the double plot, a fairly compact structure. For the Lear-plot the act may be considered as extending from Scene 1 to Scene 6; for the Gloucester-plot, from Scene 3 to Scene 7. Making a double order, we may sketch it as in the accompanying diagram:

It is to be noted that the treatment of the two plots is in this act different in kind: that of Lear is expository, that of Gloucester is narrative. The first has its expository climax in the hovel-scene, it falls away in the gentler tone of the farmhouse scene, ending in the old king’s exhausted sleep; the second has a steady rise through the three scenes, culminating in the blinding of Gloucester, and having an abrupt fall in the wounding of Cornwall.

But such cases of good act-structure are not to be taken as typical of Shakespeare. In Lear, for example, the other four acts are, in this respect, hopelessly inorganic. Macbeth is more evenly good, though the first three acts are the best. It is noteworthy, too, that where, as in Lear, one act surpasses the others in structural compactness, it is the third. Now the third act has for its nucleus the climax of the play as a whole, and it can thus hardly help having a well-marked rise and fall. However, an act may be well constructed and not have both rise and fall – everything depends on what is its position in the play. Take the first two acts of Macbeth; Act I may be thus summarized:

- SCENE 1. Witches. Introductory suggests the “tone” of the play.

- SCENE 2. Camp. Introductory exposition.

- SCENE 3. Witches, Macbeth, and Banquo. Exciting force.

- SCENE 4. Duncan, his generals, etc. Exciting force strengthened by partial fulfilment of the witches’ prophecies, which increases Macbeth’s confidence in them.

- SCENE 5. Lady Macbeth resolves on the murder of Duncan. This initiates the rising action.

- SCENE 6. Duncan received by Lady Macbeth.

- SCENE 7. Lady Macbeth strengthens Macbeth’s resolution.

Here the first scene is merely preliminary – like the striking of chords in music; the second is introductory; the third and fourth present the exciting force; the fifth, sixth, and seventh present the first stages of the rise. The act is perfectly compact and ends at exactly the right moment.

Compare now Act II.

- SCENE 1. Expositional of Macbeth’s highly wrought state.

- SCENE 2. Contrasting sketch of Lady Macbeth’s mood. Macbeth enters, having done the murder. The knocking on the gate.

- SCENE 3. The discovery of the murder. Flight of Malcolm and Donalbain.

- SCENE 4. Ross and Macduff discuss the murder. Macduff will not attend Macbeth’s coronation.

The act, in contrast with the preceding, has a rise and fall: it works up to the murder and presents the beginning of the reaction from the deed as shown on Macbeth and on those about him. Taken in greater detail, it has two points of supreme tension: the first in Scene 2, the second in Scene 3. The first part of Scene 1, the talk between Banquo and Macbeth, is skilfully managed so as to be pregnant with suggestion. Banquo’s frank remark, “I dreamt last night of the three weird sisters,” recalls the theme of the rising action, while Macbeth’s quick, guilty answer, “I think not of them,” is in marked contrast. There follows Macbeth’s soliloquy – really a separate scene, and paralleled by the soliloquy of Lady Macbeth at the beginning of Scene 2. After Macbeth enters, having killed Duncan, the first point of tension is reached; when the knocking commences there is a sudden relaxing. The porter’s entry makes a break, then the second rise begins, culminating in the discovery of the murder. From this point the tension relaxes again.

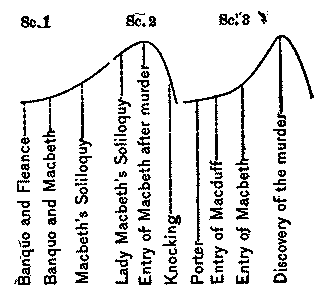

Thus the movement of this act is seen to be quite different from that of the preceding one, and yet different from Act III. If they were to be symbolized in diagrams, they would be about as follows (the Roman numerals indicate acts; the Arabic, scenes):

One more point is to be noted. It was seen in the Medea of Seneca that each act had toward its close some suggestion of the action that was to follow in the next. The same thing may be observed at the end of almost any of the acts in Shakespeare’s plays. Of the three acts just analyzed, the first closes with the criminal resolve of Macbeth and his Lady; the second has the scene with Macduff, which is subtly suggestive of his antagonism to Macbeth; the third blocks out the three main forces of the return action.

One might multiply instances of such secondary, anticipatory rise. A notable exception is found in Romeo and Juliet, in the position of the street brawl scene, wherein Tybalt is killed. We should expect it at the end of Act II instead of at the beginning of Act III. It would have given exactly the note of warning needed to intensify the scenes of the climax, yet would not have trenched so closely upon these scenes. The third act would then have begun with the orchard scene, and would have gained the jewel-like unity that is the concomitant of singleness of impression in complexity of material.

In studying act-structure, however, it must of course be remembered that the absence of a curtain made the divisions between the acts much less marked then than now. Yet the case of Macbeth shows that structural act-unity could be, though it seldom was attained by Shakespeare.

The fact is, we must not expect from Shakespeare perfection of structure. In seeing and seizing upon the essential dramatic moments in his theme he was almost unerring, but in the working out he was usually careless – possibly he was really indifferent, conscious that he possessed the “one thing needful.” Certainly the attempt to deduce laws from his act-structure gives, in the main, only negative results, whereas a study of the dramatic moments – what we have called the logical divisions – of his dramas is exhaustlessly fruitful.

Our modern drama has a character intermediate between the French seventeenth century and the English Elizabethan and Stuart drama. Each act has greater complexity than had the French, greater compactness than the English. Ibsen, in so many respects affiliated with the Greek drama, usually preserves the unity of place and sometimes that of time, as in Ghosts, and each act is individual in its presentation of some phase of the theme. Sudermann’s dramas are models in cleanness of construction, and they have the effectiveness that comes of masterly technique. In Wildenbruch’s Heinrich und Heinrich’s Geschlecht, his latest and perhaps his strongest drama, the act-structure is remarkably compact. The play is built up about the humiliation of the emperor at Canossa and is in two “evenings,” each forming a play by itself, of which the first is the more powerful. An analysis of its acts makes an interesting contrast with the Shakespearean form. It has a prologue and four acts.

Prologue. This shows Heinrich when a boy of ten. It serves to give an insight into his original, unperverted nature, and thus to invoke the sympathies of the audience.

Act I. The State House in Worms. King Heinrich returns from a victorious campaign against the rebellious Saxons. Messengers from the Pope arrive, refusing to grant his request for the emperorship, and censuring him for his evil courses. He sends back a message of defiance couched in studiedly insulting terms. The act is chiefly expositional, presenting the two great factors in the struggle that is to ensue, namely, the king’s intense love for his people and the radical antagonism between his nature and ideals and those of the Pope.

Act II. There are two scenes, the first in Rome, the second in Worms.

Scene 1. Pope Gregory is giving judgment on the penitents brought before him. Heinrich’s defiance reaches him. He wavers between the dictates of wordly ambition and those of the spiritual vision.

Scene 2. Heinrich is under the Pope’s ban, but bitter and unyielding. The children of Worms come out with Christmas gifts for the little prince, his son. Softened by this evidence of their love, Heinrich resolves for their sakes to humble himself before Pope Gregory, and secure tranquillity for his people.

Act III. Canossa.

Scene 1. An audience room in the castle. Gregory is beset by the Saxon faction, enemies of Heinrich, who offer to depose him and let the Pope create an emperor who shall be a tool of the church. As Gregory wavers before the temptation to grasp at temporal power, it is announced that King Heinrich has come to do penance.

Scene 2. Another audience room. After three days of struggle with conflicting motives, Gregory admits the royal penitent and recalls his curse. Heinrich, at the height of spiritual exaltation, learns of the Pope’s dealings with the Saxons, and the perception of this double dealing shatters his faith. His mood changes to one of hard cynicism, and he leaves the presence determined to gain the emperorship by force of arms.

Act IV. Rome. A fortified tower where the Pope has taken refuge. Heinrich enters the city with his army. In disguise, he visits Gregory and asks him to crown him emperor. Gregory refuses, and Heinrich goes, to set up a new pope who shall do his will. Gregory dies, while from below are heard the cries of the populace, “Emperor Heinrich and Pope Vibert!”

From this epitome it will be seen how each act presents one phase of the subject treated. The first suggests the factors in the problem; the second presents the two great protagonists, Heinrich and Gregory, showing how each is torn by conflicting impulses; the third brings the problem to its issue; the fourth presents the provisional solution, which the second part of the play is to bring in question, but which affords temporary stability.

Among modern French work, an example of beautiful act-structure is Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano de Bergerac, which, though called a “heroic comedy,” has a partly tragic theme and the structure of serious drama. It has five acts, each located in a single place: the first, at the Hotel de Bourgogne; the second, at Rageneau’s bakery, a rendezvous for Bohemian Paris; the third, a street before a house; the fourth, a camp at the siege of Arras; the fifth, a convent garden. Each act is a wonder of construction, being highly complex in material, yet close-knit, with no tendency to straggle or fall apart. The first two acts have each a central climax, with a secondary rise toward the close, anticipatory of the following act. The third act has the central climax, but the secondary one is less marked. The fourth act is constructed like a fifth act, with a central climax and a sudden fall to a catastrophe; but the curious double nature of the hero’s activity makes this conclusion only partial, and the brief fifth act is needed for the final resolution.

Summarizing: the division into acts has been called mechanical, in distinction from those logical divisions that are grounded in the development of the theme itself. In the Senecan drama, however, and in the classic French drama modelled thereon, each act has a lyric unity not found in the freer, more epic English drama. The best of the modern work combines the complexity and variety of the English manner with the more careful form of the French.

(2) The Scenes

The word “scene” has several meanings. It may denote merely the place in which the action occurs; it may refer to the entrances and exits of the persons; or it may mean such a section of the play as, in virtue of its significance, constitutes a unit in the treatment. According to French usage, any change in the number of persons on the stage, either by addition or diminution, makes a new scene. In common English usage, a new scene is indicated when the stage has been cleared and a new entrance occurs. The place of the action may or may not be changed. Thus, in Macbeth, Act II, the first three scenes occur in the same place, a court of the castle. The first scene would, according to French usage, be three scenes: one with Banquo and Fleance; one with Banquo, Fleance, and Macbeth; one with Macbeth alone. It is in our editions indicated as a single scene, because the entrances and exits overlap; but between Macbeth’s exit and the entrance of Lady Macbeth the stage is clear, hence a new scene is made. Either method of division has drawbacks. The French method often gives importance to an exit or an entrance – that of a servant, for instance – which does not make a real break in the action, and almost always there will be several, sometimes a dozen, of these little, mechanical scenes, going to make up what we may call the logical scene – that is, the scene which develops one phase of the subject. On the other hand, the English method sometimes leaves unemphasized an entrance or an exit that is of great importance, and we have really two logical scenes in one mechanical one. Thus in Macbeth, Act III, Scene 1, there are three distinct parts: (1) Banquo alone, (2) Banquo, Macbeth, and the court, (3) Macbeth and the murderers.

When, therefore, we say that the scene should have in little what the act and the play has in large, – a compact, organic structure with a “beginning, middle, and end,” – it is of the logical, not the mechanical scene that we are speaking.

If Shakespeare is weak in act-management, he is strong in scene-management. Perhaps this is because the scene is small enough to be kept in view as a whole, even by the careless and rapid worker that Shakespeare often was; but, whatever be the reason, one may choose almost at random and find a scene exhibiting fine technique.

As in the case of the act, so in the scene the rise and fall has not always the same form. Act II, Scene 3, of Macbeth has a central rise, but Scene 1 rises toward the close, Scene 2 falls toward the close, and the three scenes, following Freytag’s method, might be thus diagrammed:

and Scenes 1 and 2 ought, logically, to be taken either as four scenes or as one great scene in four parts, for Macbeth and his wife count here as one person, and their two soliloquies are complementary parts of the continuous rise to the murder itself.

In some ways, the words “rise” and “fall” are not helpful, however, and it almost seems unfortunate that Freytag imposed them on dramatic criticism. They are purely figurative, and figurative expressions are misleading when allowed to harden into formulas. As just used, they referred to the tension of the actors in the scenes, and hence of the audience as it follows the action. Thus Scene 1 begins quietly, with Banquo’s words to Fleance, the conversation with Macbeth has more tension, and the soliloquy reaches a spiritual tumultuousness that goes over, on the same pitch, though with difference of tone, into the next scene, and increases on Macbeth’s reëntry after the murder. The knocking on the gate acts like a dash of cold water: it breaks the continuity of mood and produces a sudden relaxation of tension.

For another instance of good scene-structure, take Romeo and Juliet, Act III, Scene i:

Introduction. Benvolio and Mercutio by their casual talk prepare us for what is to follow:

“The day is hot, the Capulets abroad, And, if we meet, we shall not scape a brawl.”

Exciting Force. Tybalt and other Capulets enter; a dispute arises between Tybalt and Mercutio.

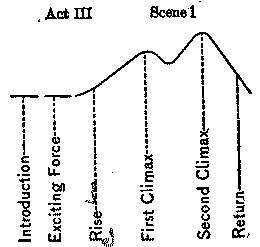

Rise. Romeo enters, bears Tybalt’s insults, and tries to calm him.

First Climax. Fight between Tybalt and Mercutio, Mercutio mortally wounded. The news of Mercutio’s death overcomes Romeo’s self-control.

Second Climax. Reëntry of Tybalt. Romeo defies him, they fight, Tybalt is killed.

Return and Resolution. Entry of the populace, with Montagues, Capulets, and the prince. The guilt of Romeo’s action is argued, the prince decides against him and banishes him.

The scene, with its two climaxes, might be thus diagrammed:

In the above scene, the words “rise” and “fall” have regard not only to the inner excitement of the participants, but to the outer events that advance the story.

In other cases the entire scene is broad exposition of spiritual states. Thus, in Lear, Act III, Scene 4, we have an elaborate study of the old man’s madness. The beginning is quiet, but by the end of his first long speech the king has worked himself up to an excitement whose character he himself recognizes:

“O, that way madness lies; let me shun that; No more of that.”

He becomes outwardly calm again, but the entry of Edgar feigning madness brings before his eyes the very madness he fears for himself, and perhaps draws him on toward it. At all events, his excitement grows again until it reaches the frenzy in which he cries, “Off, off, you lendings! come, unbutton here,” and tears away his clothes. This is the point of greatest spiritual tension in the scene. Gloucester’s entrance makes a break, and brings to the front Edgar, whose feigned ravings drop to the whimpered refrain, “Poor Tom’s a-cold,” “Tom’s a-cold,” while Lear’s fury subsides to a dazed quietude. Here the words “rise” and “fall” refer wholly to the spiritual intensity of the scene.

Summing up: the play, as a whole, is like an organism: it is articulated into acts, which are in turn articulated into scenes. Each act and each scene has its own individual completeness – a completeness which is, however, subordinated to that of the whole of which it forms a part. The scenes fall naturally into larger or smaller groups, and cannot be considered out of their position without in some fashion having violence done them. Each scene, regarded as a unit in a greater whole, resembles not one brick in a straight wall, but one stone in an elaborate arch: the form of the stone will be determined by the point in the arch at which it is placed and the purpose – whether this be ornament or support – which it serves.